by Dragana Favre

*

https://www.brainzmagazine.com/executive-contributor/dragana-favre

*

Ontology of What Disappears

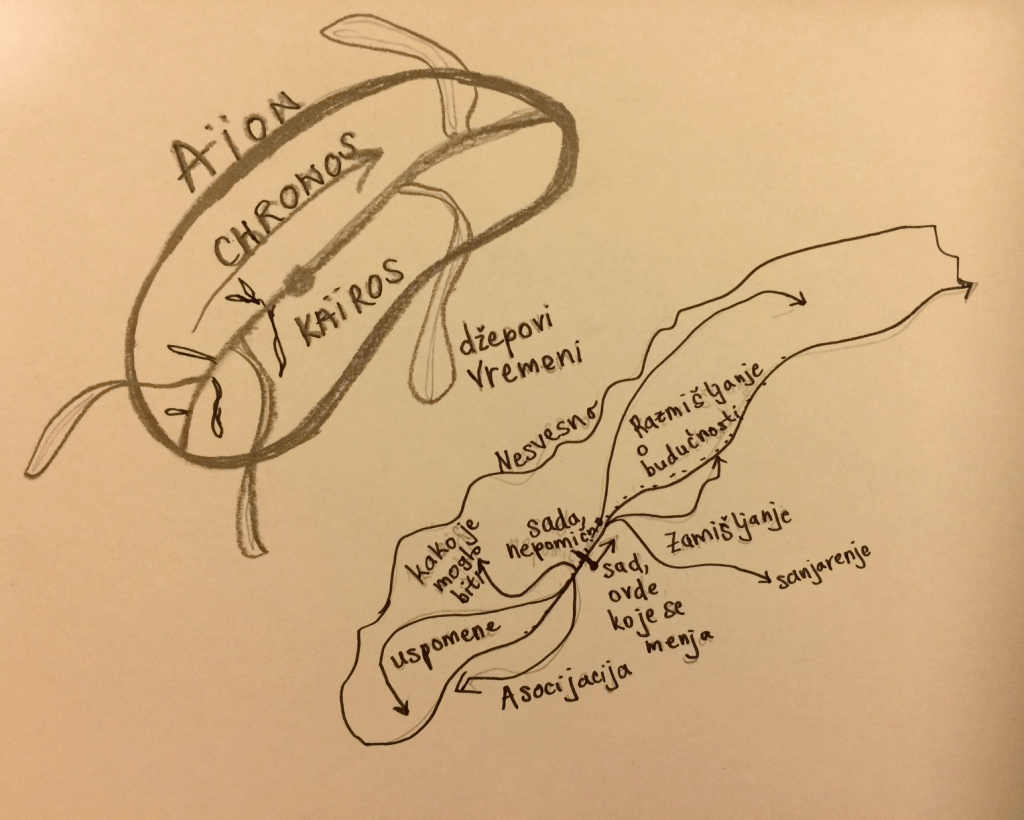

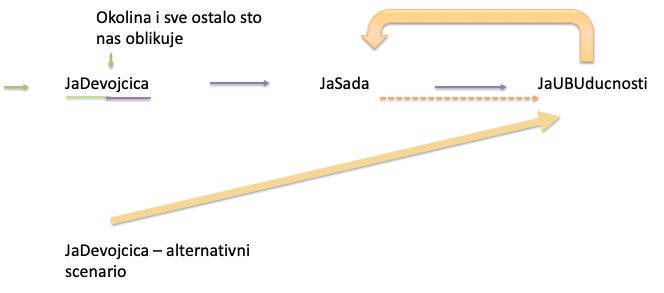

In contemporary cinema and literature, we often encounter motifs of ephemeral characters—entities that exist only temporarily, within limited frameworks of time, space, or meaning. Such characters are particularly intriguing when viewed through the prism of time loops (for example, the exceptional German series Dark), but also when compared to the way physics and mathematics employ temporary constructs to describe and understand reality. This similarity becomes even more profound when transferred into the Jungian realm of the psyche, where personality itself functions through symbolic, transient forms.

In narratives based on time loops, characters often exist solely within the repetition of a single temporal interval. They lack “external” continuity: their existence is conditioned by the rules of the loop. Once the loop is broken, they vanish or lose their identity. These characters are ephemeral not because they are weak or insignificant, but because their ontological status is bound to the structure of time itself. They exist only as long as time is being counted, much like auxiliary quantities in mathematics.

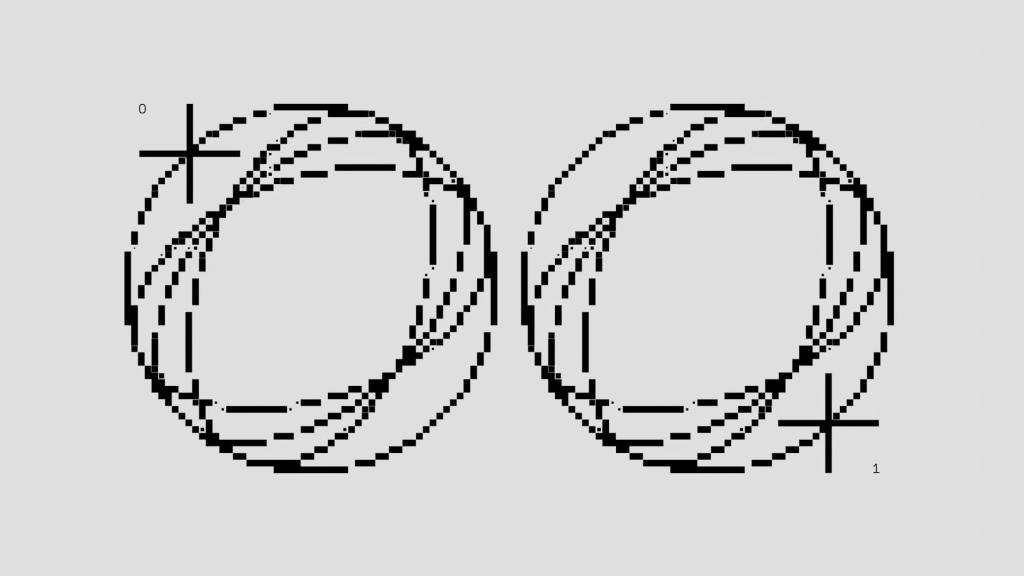

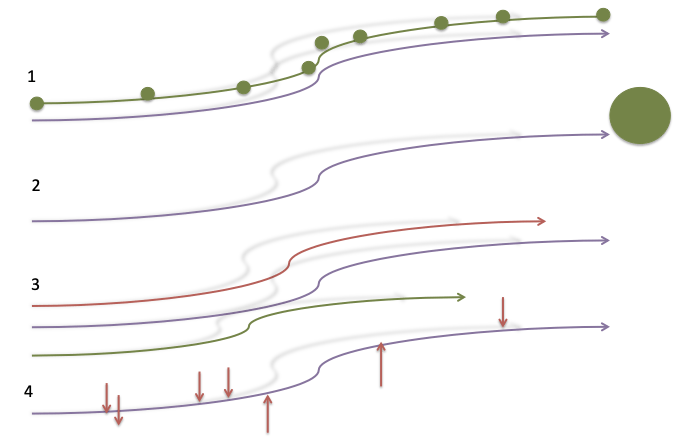

In mathematics and physics, we often introduce numbers, variables, or entire expressions that have no direct physical meaning, yet are necessary for solving a problem. For example, in an equation we may add and subtract the same term:

x² − 4x = 0

x² − 4x + 4 − 4 = 0

By adding the number 4—which is later “cancelled out”—we enable factorization and make the equation easier to solve. This number 4 is ephemeral: it does not change the final result, but without it the process of solving would not be possible. Similarly, in physics we introduce imaginary numbers, auxiliary coordinate systems, or idealizations (such as point masses or frictionless surfaces) that do not exist in reality, but allow reality to be calculated and understood.

Ephemeral characters in time-loop stories serve the same function. They are the “added term” in the narrative equation. Their fate is to repeat, reset, or disappear, but through them the main character—or the observer—comes to understand the system in which they are situated. Just as an auxiliary number is neutralized at the end, the ephemeral character is often erased from the final outcome of the story, leaving behind only knowledge or a shift in consciousness.

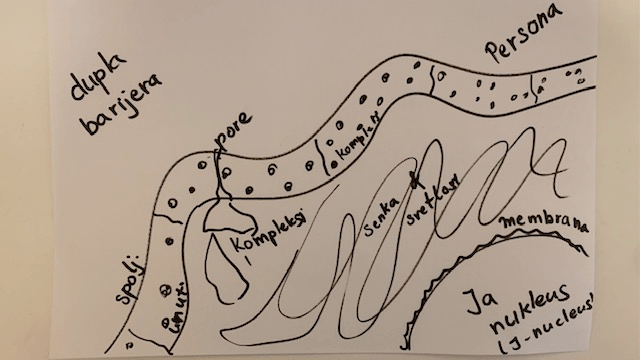

When we transfer this analogy into Jungian psychology, we enter the world of symbols, archetypes, and the unconscious. According to Jung, the psyche is not a linear and stable structure, but a dynamic field in which various contents appear, disappear, and reappear. Complexes, dreams, and symbolic figures are often ephemeral, emerging only at a particular stage of psychological development or within a specific “inner time.”

In this sense, the Jungian psyche functions as an internal time loop. Certain patterns of behavior, emotional reactions, or dreams repeat until the individual becomes conscious of their meaning. Dream figures, shadows, animus, or anima can be viewed as temporary constructs of the psyche—auxiliary variables that make it possible to “solve the equation” of individuation. Once their message is integrated, they lose their power or disappear, just like terms in a mathematical equation that cancel each other out.

The ephemeral character—whether in a time loop, a mathematical formula, or a psychological symbol—is not a flaw in the system, but a necessary part of it. It exists so that the process can unfold. Its transience is precisely what gives it meaning. In the Jungian world, as in physics, truth is often found not in permanent objects, but in relationships and processes. What disappears leaves its trace in understanding, not in form.

Ultimately, the similarity between these domains shows that the human mind—whether creating scientific models, mathematical formulas, or narratives about time—employs the same strategies: it introduces temporary figures in order to arrive at lasting insight. The ephemeral is not the opposite of meaning—it is its necessary condition.

*

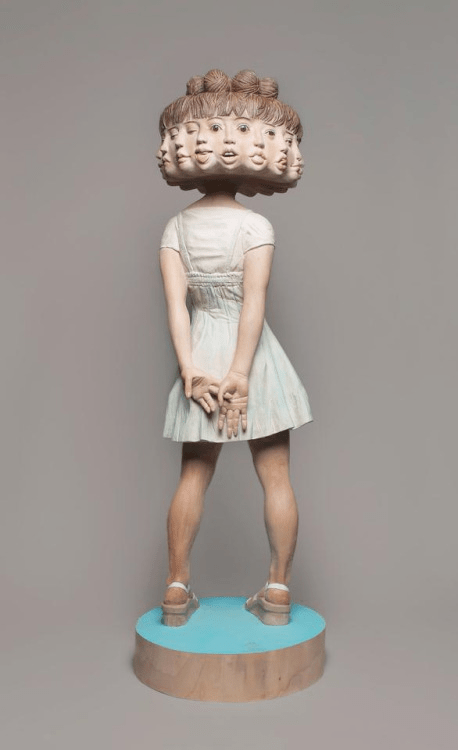

The Shadow of Injury and the Strength Hidden Within It: Between Defense and Ethical Choice

From a Jungian perspective, experiences of deep injury—humiliation, neglect, the sacrifice of one’s own needs, prolonged emotional deprivation—rarely remain only in the form of a clear narrative. More often, they withdraw from direct awareness and organize themselves as a complex, as a psychic “concentration” of affect and meaning that continues to live independently of the ego’s will. What was unbearable to feel, to acknowledge, or to find a place for in relationship slips into the zone Jung calls the Shadow: not necessarily as “evil,” but as that which was rejected, unclaimed, cut off from identity in order to survive. In this sense, the Shadow is not merely a repository of undesirable impulses, but also an archive of what was not allowed to exist—and for that very reason it becomes a source of tension, pressure, and unintegrated energy (Jung, 1959; Jung, 1969).

In that space, defenses often form that outwardly may resemble narcissistic patterns: a need for control, hypersensitivity to criticism, rigid self-sufficiency, an exaggerated narrative of one’s own strength or specialness. If only the surface is observed, it is easy to reduce everything to “narcissism” as a characterological defect. But from a clinical perspective, especially when developmental background is taken into account, narcissistic organization can be understood as a secondary stabilization—an attempt to preserve a fragile core of the self from renewed disintegration, shaming, or worthlessness. In that sense, grandiosity is not the opposite of vulnerability, but its mask; and contempt and distance are often not coldness, but protection against renewed humiliation. Along this line of understanding, Kohut views narcissistic structures as attempts at self-regulation and the protection of identity continuity, while Kernberg emphasizes that the grandiose self state is often organized around defenses against envy, shame, and helplessness (Kohut, 1971; Kernberg, 1975).

Yet here the most important point is easily overlooked: defenses do not conceal only pain, but also strength. What has been repressed is not merely the memory of injury, but also the primary energy of the reaction to it—rage, anger, the need for rectification, the desire for justice or revenge, the urge to restore balance and reclaim dignity. In Jung’s language, libido does not disappear; it relocates, condenses, changes form, and seeks a channel. When that force lacks a symbolic form and a conscious “container,” it acts autonomously: it erupts as an affective storm, as a magnetism that attracts and unsettles, as pressure on others, as a need to reverse a situation at any cost, or as a seductive allure carrying a taste of danger and a promise of power. The Shadow then is not only dark; it is also potent. Within it lie both destructive and life-affirming possibilities, and the paradox is that the same energy that can wound can, if integrated, become fuel for individuation (Jung, 1959; Jung, 1969).

This is why, in relationships, what is transmitted is often not only the story of an old wound, but its energetic charge. A wounded person may unconsciously “bring” into a relationship an intensity that others experience as heaviness, as a challenge, as a call to struggle, as a need to prove or correct something. Sometimes this is felt as the strength of pain, sometimes as seductiveness, sometimes as cold dominance, and sometimes as a fascinating depth. In all these variants, the same phenomenon is at work: the unintegrated energy of the Shadow spills beyond the boundaries of the ego and becomes an interpersonal event. Other people then, often without knowing why, begin to react—to defend themselves, attack, idealize, submit, or attempt to “fix” what is not theirs. Thus a chain of stimulation and reaction emerges in which trauma finds a new stage: instead of being understood, it is repeated.

At that moment, what is essentially ethical in the Jungian sense appears: choice. Not the choice of whether we will have this strength—because it already exists—but the choice of what we will do with it. One possibility is rectification understood as an unconscious settling of accounts: to “collect” through other people or situations what was once taken away, to turn humiliation into humiliating others, to replace helplessness with control, to transform a wound into a right to take. The other possibility is rectification as a conscious act: acknowledging the injury without turning it into a license, taking ownership of the energy without pouring it out onto others, finding a symbolic and creative form for what is raw and explosive. Jung warned that moralizing the Shadow does not lead to integration; it is merely another form of repression. Integration means acknowledging, “This is in me”—and then adding the equally important continuation: “I am responsible for the consequences” (Jung, 1959).

Breaking the chain of stimulation does not mean becoming weak or passive. On the contrary, it often takes greater strength to renounce unconscious revenge than to enact it. It is the discipline of an ego that can endure its own anger without immediate discharge, and that can endure its own desire for justice without turning justice into punishment. Such an ego learns to distinguish dignity from domination, boundary from retaliation, and respect from submission. Then strength ceases to be a weapon and becomes a capacity: the ability to influence, to stand behind oneself, to say “no,” to protect what is vulnerable, and to remain aware of one’s own impact.

From there, the most mature formulation opens up: respecting others does not merely mean being “good,” but being aware that personal energy carries weight and consequences. Responsibility in this context is not guilt, but authorship. The wounded person is not only a victim; they are also the bearer of concentrated strength. They did not choose this strength, but they do choose its direction. Individuation, in the most concrete sense, begins when the subject can acknowledge the Shadow as their own and decide not to delegate it to the world through unconscious power games, but to translate it into conscious acts: into boundaries, into truth, into creation, into a justice that does not have to be revenge.

References:

Jung, C. G. (1959). Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1969). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

Kohut, H. (1971). The Analysis of the Self. International Universities Press.

Kernberg, O. (1975). Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism. Jason Aronson.

*

Individuation as Movement Through the Cosmos

When we observe the solar system today, we no longer imagine it as a calm, static image from school atlases: the Sun fixed at the center, planets neatly arranged in perfect circles, everything stable and complete. Contemporary astronomy shows something entirely different. The solar system is not located “somewhere” in space; it is constantly moving through the galaxy. The Sun itself is not an immobile point, but a body in motion, drawn by the gravity of the galactic center, immersed in a vast cosmic space that both contains it and determines it. The planets do not revolve around the Sun in closed circles; together with it, they trace spiral paths through space-time. Their movement is possible only because there is a cosmos through which they move. Without that space, without that broader order, there would be no trajectory, no direction, no relationship.

This image carries profound symbolic value for understanding individuation. Jungian psychology does not view the psyche as a closed system. The psyche does not exist in a vacuum. It is always embedded in something greater than itself: in the collective unconscious, in the archetypal order, in history, the body, culture, and nature. Just as the solar system exists only within the galaxy, the individual exists only within a broader psychic cosmos. Individuation is not merely an inner process of the ego; it unfolds in relation to a space that transcends it.

The Self, in this sense, is not only the center of the psyche but also a point of relationship between the inner and the outer cosmos. It organizes psychic life, but not in isolation. The ego relates to the Self as a planet relates to the Sun, yet the Sun itself is already in motion, already part of a larger whole. This means that the individual must not only discover an inner center, but also endure the fact that this center itself is situated within something greater. Individuation, therefore, is not a process of withdrawing into oneself, but of situating oneself within a cosmic order.

When the ego loses awareness of this wider space, distortion arises. Just as a planet that ignored the galaxy and imagined the entire cosmos ending at its own orbit would misinterpret its movement, so too does an ego that encloses itself within a purely personal perspective lose its sense of proportion. Complexes then emerge as false centers. They not only assume the role of the Sun but also erase awareness of the cosmos itself. Everything becomes personal, enclosed, compressed into the narrow space of inner drama. Movement loses its breadth and becomes compulsion.

In Jungian terms, suffering often arises precisely from this narrowing of space. The psyche demands a wider horizon than the ego allows. When life is reduced to a single identity, a single role, a single story, the inner cosmos collapses. Symptoms then are not merely signals of an incorrect trajectory, but also cries for space. Depression, for example, often carries an experience of infinity, emptiness, cosmic distance. It can be a painful yet necessary encounter with the fact that the ego is not the measure of all things, that there exists something immense, indifferent, yet structuring.

Individuation therefore requires not only a relationship to the center, but also a relationship to space. It presupposes the capacity to endure the openness of the cosmos, the uncertainty of movement, the absence of a final support. Just as the solar system does not move toward a clearly visible goal but follows laws that transcend human comprehension, so individuation has no clear image of an end. It unfolds in time, in change, in continual adjustment to a broader order.

To be individuated does not mean to be separated from the cosmos, but to be consciously situated within it. It means accepting one’s own limitation as well as one’s own participation. The human being is neither the master of the cosmos nor an insignificant point within it. He or she is a participant. Dignity does not arise from centrality, but from the capacity to endure the truth of one’s place.

In this sense, the individual does not exist despite the cosmos, but because of it. Just as the trajectory of a planet has meaning only in relation to the vast space through which it moves, so too does human life acquire meaning only when it is seen as part of a wider, unconscious, archetypal reality. Individuation then becomes an act of cosmic humility: a consent to be in motion, in relationship, in a space that surpasses us, yet also carries us.

*

Behind the Veil of Space-Time: Physics as a Myth of the Self

Quanta Magazine recently released a video essay, Space-Time: The Biggest Problem in Physics (Quanta Magazine, 2024; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RIqVnFtOSr4), which caught my attention in a serious way. At first glance, it looks like “just another” popular-science piece about space, time, and quantum gravity. But if we read it through a Jungian and cosmopsychic lens, something else appears behind the standard story of theories and equations, something closer to a mythic narrative about the dissolution of the old world and the search for a new center of meaning.

Our everyday framework, space and time as a neutral stage, begins to fall apart at the Planck scale. There, general relativity no longer applies, quantum mechanics refuses to cooperate, and phenomena like black-hole entropy, holography, and dualities suggest that reality is not what common sense takes it to be. In Jungian terms, this follows the classic descent-and-return structure: the ego loses its grounding, the old “stage” dissolves into nigredo, a new guide appears (albedo), a pattern that links opposites comes into view (citrinitas), and a symbol of unity slowly takes shape (rubedo). In cosmopsychism, however, this process belongs not only to an individual psyche—it is a way in which the “psyche of the world” becomes aware of itself through our theoretical images. The question “Is space-time fundamental or emergent?” becomes a psychological koan: is the ego simply a window into a deeper Self, one that is both personal and cosmic?

The film begins in the zone of dissolution—nigredo. At the Planck length, physics itself “breaks down”: the singularities of black holes and the Big Bang mark points at which general relativity becomes self-inconsistent. Quantum mechanics, with its probabilities and amplitudes, refuses to fit onto the smooth geometry of space-time. This clash of two grand regimes, continuous geometry and discrete quantum play—reads like the archetypal conflict between the Father-Law and the subversive energy of the Trickster. It is not merely a technical problem; it is a phase in which the old order must melt before a new one can emerge.

Just when everything seems blocked, a guide, the psychopomp, appears, and here it takes the form of information. Instead of asking “What is the correct geometry of space-time?”, the narrative shifts toward entropy and information. Black holes behave as thermodynamic objects; their entropy is proportional to the area of the horizon, not its volume (Bekenstein, 1973; Hawking, 1975). This is a powerful reversal: the key to the deepest geometry appears not in a new geometric intuition, but in an informational principle. Jung would call this a symbolic transformation: what we once thought of as “pure matter” suddenly reveals itself as inseparable from meaning and information. In a cosmopsychic reading, this suggests that the anima mundi, the soul of the world, cannot be thought separately from relational order and information. Geometry and information cease to be two separate domains and become two languages of the same underlying reality (Bousso, 2002).

Then comes the Trickster. The holographic principle and the concrete AdS/CFT duality claim that a theory of gravity in some “interior” volume can be fully equivalent to a non-gravitational quantum field theory living on a lower-dimensional boundary (Maldacena, 1998; Susskind, 1995). Inside becomes outside, surface carries content, gravity transforms into non-gravitational dynamics. These reversals of hierarchy bear the unmistakable signature of the Trickster: both/and, inversion, a playful laughter at our overly literal assumptions. For Jungian imagination, this is medicine against reification: a reminder not to confuse our image—say, the smooth manifold of general relativity, with reality itself.

As this chaos of reversals begins to organize itself, the film introduces a motif it treats as a possible key: perhaps space-time is not fundamental at all, but arises from patterns of quantum entanglement. Entanglement is increasingly described in the literature as the “glue” that builds geometry: relations are primary, and “objects in space” are derivative. This is citrinitas, the gentle dawning of a new perspective. We no longer identify with the things occupying space; instead, we identify with the network of relations that allows space-time to appear in the first place. This insight fits well with new approaches to “quantum geometry,” where physical quantities are computed from algebraic structures and scattering amplitudes without explicitly invoking space-time itself. The film hints at this, especially through remarks by Vijay Balasubramanian and recent reporting (Wired / Castelvecchi, 2024).

In Jung’s language, quantum entanglement and its “nonlocality” evoke the idea of the unus mundus: a unified psycho-physical order in which inner and outer, subject and object, are not two separate realms but two aspects of a single process (Jung, 1959a; 1963). Synchronicity is how the unus mundus peeks through our linear, causal stories (Jung, 1952/2001). Holography and entanglement act as physical analogues: patterns of correlation belonging simultaneously to “geometry” and to “information.” For cosmopsychism, this is expected: if the cosmos is fundamentally one mind (Goff, 2017; Nagasawa & Wager, 2020), then local separations are real enough for everyday life but not ontologically deepest.

As the film draws to a close, various strands, thermodynamics, dualities, algebraic formalisms, quantum information, begin to form something like a mandalic pattern. Space-time appears as a possible “effective field,” an order-parameter describing a deeper informational and algebraic substrate. In alchemy, rubedo marks the final stage: coniunctio, the union of opposites around a new center. Jung calls this the Self, symbolized by mandalas, quaternities, or axis mundi structures (Jung, 1959b; 1963). In the film’s context, the “mandala” is the structural coherence in which thermodynamics (entropy/area), geometry, quantum information, and dualities begin to mirror one another. Opposites no longer cancel each other out; they become facets of a broader field.

Within this narrative we can easily recognize a “drama of archetypes”: the Shadow in singularities and our collective blind spot to the limits of our theories; the Psychopomp in entropy and informational principles guiding us across ontological layers; the Trickster in dualities and holographic reversals; the Wise Old Man in mathematical structures that feel like a foreign language but teach through symmetries, groups, and categories; and finally the Self, as the pattern of unity in which contradictions are held and transformed rather than annihilated.

A cosmopsychic reading sharpens the picture further: the deepest “subject” is not the individual ego but the cosmos itself, and individual minds, including scientific communities, are local perspectives within a larger mind (Goff, 2017; Nagasawa & Wager, 2020). In this frame, the tension between general relativity and quantum mechanics is not only an external puzzle but a mode of the world-psyche differentiating itself. Holographic equivalence between volume and boundary becomes a kind of anamorphosis: the One showing itself from different vantage systems while the underlying content remains the same. Entanglement becomes the formal signature of unity: relations precede “things.”

This approach also carries ethical weight. If the world is in some sense “ensouled,” then knowing is not mere observation, it is participation. The film models this kind of participation well: it neither romanticizes mystery nor trivializes it. It seeks bridges that can be tested (entropy bounds, dualities, precise relations between information and geometry), yet leaves space for imagination and mythopoetic understandingm something Hillman and other Jungians saw as essential to a fuller understanding of psyche (Hillman, 1975, 1979; von Franz, 1980).

Synchronicity as an “acausal connecting principle” can also be seen in the realm of form: the striking match between horizon area and the amount of information, or between boundary theories and bulk dynamics, feels like a formal “coincidence” that opens entire research programs. Of course, physicists derive these relations rigorously, but the meta-pattern, that information and geometry repeatedly appear as inseparable, would have fascinated Jung. Cosmopsychism offers a way to understand this without magical overreach: one subjectivity refracting itself through multiple descriptive languages.

At the same time, boundaries matter. Archetypal analysis can easily overextend: not every reversal is a Trickster, nor every circle a mandala. Cosmopsychism is a serious metaphysical stance, but not a proven “theory of everything.” And physics itself has multiple possible futures: some authors, like Latham Boyle, believe space-time may eventually be rehabilitated rather than replaced; the film places this perspective fairly within the broader series (Quanta Magazine, 2024). Such pluralism is part of a mature stance, scientifically and psychologically.

In the end, Jung’s idea of individuation offers a fitting metaphor for what the film implicitly demonstrates. Individuation is not the glorification of the ego but its right relation to the Self. Translated into epistemic ethics: theorists must be willing to let go of cherished frameworks (classical manifolds, strict locality) when evidence and coherence demand it, without collapsing into formlessness. The “path to quantum gravity” is therefore not only a technical challenge but also an initiatory process: a community learning to participate in the self-articulation of the world-mind with humility, play (Trickster), and fidelity to symbols that actually work (entropy laws, duality dictionaries, new algebraic structures). In Jungian terms: the gold of rubedo is not a final formula, but the ongoing practice of holding opposites until a higher-order image appears to contain them. The film ends not with a solved riddle but with a centered stance, a mandala-like equilibrium from which new experiments, new theorems, and new myths may grow.

References

Bekenstein, J. D. (1973). Black holes and entropy. Physical Review D, 7(8), 2333–2346.

Bousso, R. (2002). The holographic principle. Reviews of Modern Physics, 74(3), 825–874.

Goff, P. (2017). Consciousness and fundamental reality. Oxford University Press.

Hawking, S. W. (1975). Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 43(3), 199–220.

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning psychology. Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1979). The thought of the heart and the soul of the world. Spring Publications.

Jung, C. G. (1952/2001). Synchronicity: An acausal connecting principle. In C. G. Jung & W. Pauli, The interpretation of nature and the psyche. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1959a). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1959b). Aion: Researches into the phenomenology of the Self. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1963). Mysterium coniunctionis. Princeton University Press.

Maldacena, J. (1998). The large-N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics, 2, 231–252 (preprint 1997).

Nagasawa, Y., & Wager, K. (Eds.). (2020). Panpsychism. Cambridge University Press.

Quanta Magazine. (2024, September 25). Space-Time: The Biggest Problem in Physics [Video explainer]. (Producer: Emily Buder; Featuring: Vijay Balasubramanian).

Quanta Magazine. (2024, September 25). The Unraveling of Space-Time [Series hub]. Quanta Magazine / Wood, C. (2024, September 25). Can Space-Time Be Saved? (Interview with Latham Boyle).

Susskind, L. (1995). The world as a hologram. Journal of Mathematical Physics, 36(11), 6377–6396 (preprint 1994).

von Franz, M.-L. (1980). Alchemical active imagination. Spring Publications.

Wired / Castelvecchi, D. (2024, November 3). Physicists reveal a quantum geometry that exists outside of space and time. (Includes remarks by V. Balasubramanian).

*

Purpose as a Lighthouse … And as Gravity

Imagine for a moment that your consciousness is a small, luminous boat floating on a vast, dark ocean. That ocean is what Jung called the unconscious, personal and collective, a depth that holds instincts, memories, archetypes, and all the stories humanity (and before humanity) has ever told about itself. Jung often used water, especially the sea, as a symbol for these depths: endless, mysterious, and full of life that is mostly invisible from the surface.

On a calm day you drift peacefully. On a stormy one you feel thrown around by waves of emotion, old patterns, and invisible currents you can’t quite name.

So the real question is: what keeps this little boat from drifting forever?

From a Jungian point of view, purpose is not just a motivational slogan. It’s a psychic axis. When something truly matters to us, not just “I should do this” but “I cannot not move in this direction”, it becomes more than a goal. It becomes a tag in the ocean: a fixed point our inner compass can recognize again and again.

Jung called the deeper organizing principle of the psyche the Self, the totality of conscious and unconscious, the center and the whole at once. Our everyday “I,” the ego, is just the small center of conscious life. The living relationship between these two, ego and Self, has been described as the ego–Self axis: the psychological line along which meaning, guidance, and correction move back and forth. When we find a purpose that resonates deeply, we’re not inventing it out of nowhere. We’re discovering a line of force that was already there in the depths. It’s like throwing a glowing buoy into the water and suddenly realizing: “Oh. There’s a current here. This is where the Self is pulling.”

Purpose then acts like gravity. Instead of the ego rowing frantically in all directions, it feels a subtle pull: this way. Even when the fog is thick, the boat can orient toward that invisible mass beneath the surface.

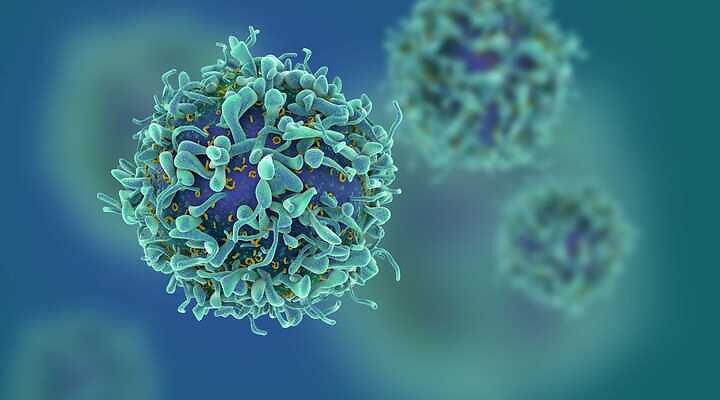

Modern neuroscience quietly agrees with Jung on at least one point: consciousness is not the whole show. Much of what our brain does is rhythmic, automatic, patterned, happening long before “I” decide anything.

Brain oscillations create internal timing grids; they organize when neurons are most likely to fire together, shaping what we notice, remember, and feel. When those rhythms click into new patterns, we often experience an “aha” moment, insight surfacing like a dolphin breaking the water.

Some studies even show interbrain synchronization: during deep conversation or collaboration, people’s brain rhythms literally begin to align. Our little boats start moving in formation.

For Jung, the psyche was always a self-regulating system that strives for balance between opposites and moves toward wholeness. Purpose, in that sense, is not imposed from outside; it’s how the deeper system “votes” for a certain direction.

The Self whispers through symbols, dreams, synchronicities. Purpose is what happens when the ego not only hears the whisper but says: All right. I’ll steer that way. In a world obsessed with productivity, it’s easy to mistake purpose for a rigid five-year plan or a LinkedIn headline. From a Jungian perspective, that’s far too small. A real purpose-axis is less like a project plan and more like a north–south line on your inner map. We can wander east and west, explore, play, make mistakes, but something in us keeps re-orienting. That axis doesn’t imprison us. It protects us from drifting everywhere and arriving nowhere.

When we lack such an axis, the ego gets seduced by every glittering thing on the horizon. New job. New relationship. New city. New identity. It feels like movement, but the deeper feeling is often one of emptiness or meaninglessness – the psychic equivalent of being lost at sea. So, how do we find our axis?

The unconscious loves images. Recurrent symbols, landscapes, or characters in dreams often point toward what the Self is trying to constellate. Intense fascination and irrational irritation often signal encounters with archetypal material, not just “random mood.” Writing, art, science, entrepreneurship: whenever you feel that mix of fear, excitement, and inevitability, you may be close to your axis. The story that keeps showing up in different clothes is usually not bad luck; it’s the psyche insisting on a lesson. This is not about fixing ourselves. It’s about listening for where the ocean is already moving, and placing our tags right there.

And, there’s the paradox: the ego is too small to be the axis, but it’s absolutely needed to co-create with it.

When the ego tries to be the captain, map, and ocean all at once, life becomes exhausting. But when it accepts its role as navigator, something softens. Decisions become less about “What will make me look successful?” and more about “What serves the direction my life is already trying to take?” In Jungian language, that is the beginning of individuation: the long, sometimes messy process of becoming who you actually are, not who you were trained to be. Not to make us more efficient machines, but to hook our small, flickering consciousness to a much larger story.

So, maybe the question isn’t: “What should I do with my life?” Maybe it’s: “Where is my inner gravity already pulling, and how can I honour that pull with one clear, visible axis?”

Because once that axis is there, the ocean is still vast, the night is still dar… but our little boat is no longer lost.

*

Why We Fall in Love with People and Ideas

Love for a person and “falling in love” with an idea look more alike from the inside than we’d think at first glance: in both cases the reward system raises the target’s value, attention narrows, memory is strengthened, and the body takes on a recognizable signature of excitement and calm in brief waves. In the romantic version, the trigger is the face and presence of another person; in the intellectual version, it’s a problem, a hypothesis, or an elegant pattern. The dopaminergic VTA–nucleus accumbens loop pushes behavior forward (“I want more”), while the ventromedial prefrontal cortex evaluates and writes the narrative of why this object of attention matters (Bartels & Zeki, 2000; Aron et al., 2005). It isn’t just a “nice feeling,” but learning: positive prediction errors (it turned out better than expected) strengthen the learning trace and send us back along the same path, whether toward a partner or an idea (Schultz, 1997).

It’s interesting to look at brain oscillations, which further complete the picture. In moments of insight (that inner “click”), EEG often shows brief bursts of gamma activity, preceded by reshaping of alpha rhythms that “close the door” to distractions and redirect resources toward relevant representations (Kounios & Beeman, 2009). That rapid functional “coherence” of widely distributed networks produces the feeling that the pieces of the puzzle suddenly hold together. Early-stage romantic infatuation also shifts rhythm: heightened arousal of the locus coeruleus–norepinephrine system, narrowed attention, and easily triggered salience of partner cues, scent, glance, message, are accompanied by a subjective “tunnel” in which everything else fades (Aston-Jones & Cohen, 2005; Fisher et al., 2006). In the intellectual case that tunnel culminates in problem-solving; in romance it seeks reciprocity and bonding, so networks for social cognition and belonging become more engaged (Aron et al., 2005).

Memory is a shared winner. Curiosity boosts hippocampal encoding via a dopaminergic “bridge” from the VTA; when we’re genuinely interested, we remember even incidental information we encounter along the way better (Gruber, Gelman & Ranganath, 2014). In romance, analogously, signals associated with a partner get privileged access: micro-events, a word, a scent, a place,readily become emotional waypoints in autobiography (Aron et al., 2005). This also helps explain why “shared rituals” (walking, cooking, music) work: rhythm and repetition stabilize networks, giving body and brain reliable inputs from which a felt sense of safety is woven.

The biggest neurophysiological differences arise from the social biology of bonding. Romantic love gets a scaffolding of oxytocin and vasopressin which, in interaction with dopamine, map the partner as special and facilitate long-term attachment; this is compellingly shown in prairie vole models and linked to human bonding and trust (Young & Wang, 2004; Carter, 2014). Intimate touch, scent, and rhythmic closeness lower autonomic arousal, raise stress tolerance, and support reconnection after conflict. Intellectual infatuation rarely has this peptidergic “cement”; it can acquire it indirectly through teamwork, mentorship, and shared community rituals, but its primary engine remains the valuation of insight, novelty, and progress (Gruber et al., 2014).

Still, there is a bridge: synchrony. When two people hold hands or work in coordination, “hyperscanning” studies record greater inter-brain coherence; the subjective feeling of closeness tracks with higher temporal alignment of neural activity (Goldstein, Weissman-Fogel & Shamay-Tsoory, 2018). In intellectual communities we see a related dynamic: seminars, labs, and creative workshops form “shared rhythms” (listening, reflection, writing) in which the group amplifies the individual’s focus. These aren’t the same networks as in intimate closeness, but the principle is similar: a shared temporal structure reduces uncertainty and makes effort easier (Konvalinka & Roepstorff, 2012).

Seen from a “neo-Jungian” angle, archetypes can be read as deep predictive priors of the mind, evolutionarily grounded sketches of relations and meanings that the brain uses to connect dots faster. Eros would then be a drive toward integration: the urge to bind separated elements into a wider order. Anima/animus projections can be understood as probabilistic expectations about the Other that speed social decisions but carry the risk of bias until they meet the “data” of the actual person. Intellectual coniunctio is the moment when disparate representations enter a common phase— a gamma burst, dopaminergic tagging, and a sense of meaning that then demands integration into habit and practice (Kounios & Beeman, 2009). In both cases, the symbolic language of the Jungian tradition and the measurement language of cognitive neuroscience can be seen as two descriptions of the same process of binding scattered parts into a form that “holds water.”

From an evolutionary perspective, the triad of sex drive, specific attraction, and attachment optimizes reproduction, cooperation, and offspring care; hence romantic love has a deep hormonal and social infrastructure (Fisher, 2004; Carter, 2014). “Love of an idea” is most likely a co-optation of the same mechanisms of curiosity and environmental exploration: rewarding novelty, better predictions, and successful problem-solving directly increases the adaptability of individuals and groups (Schultz, 1997; Gruber et al., 2014). In other words, the dopaminergic economy can bind to a person, a problem, or a landscape, the common denominator is learning that improves future decisions.

Looking ahead to the future and the Zeitgeist, the boundary between romantic and intellectual “falling in love” may become more porous: we live in an attention economy where digital rhythms easily catch our oscillations and push them into tight loops of dopaminergic seeking. At the same time, neuroadaptive practices are growing: biofeedback, deliberate breathing, and movement that fine-tune alpha–theta thresholds for creative insight and reconfiguring the salience network. Hyperscanning of teams, classrooms, and ensembles may become a tool for cultivating “collective coherence” that fosters both safe closeness and bold curiosity. However, e should not forget to keep a human measure while we learn to deliberately orchestrate our own waves.

References

Aron, A., Fisher, H., Mashek, D. J., Strong, G., Li, H., & Brown, L. L. (2005). Reward, motivation, and emotion systems associated with early-stage intense romantic love. Journal of Neurophysiology, 94(1), 327–337.

Aston-Jones, G., & Cohen, J. D. (2005). An integrative theory of locus coeruleus–norepinephrine function: Adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 28, 403–450.

Bartels, A., & Zeki, S. (2000). The neural basis of romantic love. NeuroReport, 11(17), 3829–3834.

Carter, C. S. (2014). Oxytocin pathways and the evolution of human behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 17–39.

Fisher, H. E., Aron, A., & Brown, L. L. (2006). Romantic love: A mammalian brain system for mate choice. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 361(1476), 2173–2186.

Fisher, H. (2004). Why We Love: The Nature and Chemistry of Romantic Love. New York: Henry Holt.

Goldstein, P., Weissman-Fogel, I., Dumas, G., & Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. (2018). Brain-to-brain coupling during handholding is associated with pain reduction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(11), E2528–E2537.

Gruber, M. J., Gelman, B. D., & Ranganath, C. (2014). States of curiosity modulate hippocampus-dependent learning via the dopaminergic circuit. Neuron, 84(2), 486–496.

Konvalinka, I., & Roepstorff, A. (2012). The two-brain approach: How can mutually interacting brains teach us something about social interaction? Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 215.

Kounios, J., & Beeman, M. (2009). The Aha! Moment: The cognitive neuroscience of insight. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(4), 210–216.

Schultz, W., Dayan, P., & Montague, P. R. (1997). A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science, 275(5306), 1593–1599.*

*

What Illuminates the Dream?

When we dream or imagine, images unfold in the inner theatre of the mind, bright, colored, and alive, yet no light enters the eyes. The question, seemingly simple, hides a profound mystery: what illuminates the inner images of dreams and imagination? Where does their light come from? In waking life, photons strike the retina and travel through the optic nerve to the brain, but in dreams, there are no photons, no external light, no world out there. And still we see.

Neuroscience tells us that when we dream, the same regions of the brain that process vision during waking, especially the occipital cortex, are active. The difference is that, instead of being stimulated by external light, they are stimulated endogenously. The brain becomes its own projector. It emits patterns of electrical activity that mimic the sensory codes of vision, generating what could be called “simulated luminosity.” This endogenic light has no physical photons; it is a self-sustaining fire, an inner photic hallucination. During REM sleep, this process becomes especially vivid: the visual cortex flares, the prefrontal cortex relaxes, and a world arises entirely from within. In a sense, we dream by remembering how to see.

Yet no brain scan can account for the lived experience of that inner brightness. There is a difference between describing the mechanism of a projection and standing inside the film itself. When we dream, we do not feel that neurons are flickering; we feel that light fills a space, that colors shimmer, that faces glow. The inner world seems to have its own illumination, a kind of metaphysical luminosity. This paradox, light without photons, space without extension, reveals something essential about consciousness: it is not merely a passive screen but the very condition of visibility itself. Consciousness is the light by which anything, even darkness, can appear.

Phenomenology and depth psychology meet at this threshold. Jung called this psychic radiance lumen nature, the light of nature that shines from within the psyche. It is not the rational light of intellect but the living light of the soul. When an image appears in a dream, its luminosity reflects the intensity of psychic energy flowing through it. A numinous figure seems to emit light because it carries the charge of the archetype. The brightness is not an optical illusion but a symbolic fact: energy has become visible. The dream’s light is libido made manifest.

Libido, in Jung’s sense, is not just sexual but vital, the primal current of the psyche, the élan that moves between opposites. When this current flows freely, inner images blaze with clarity and color; when it is blocked, dreams grow dim and monochrome. The dream’s brightness measures the aliveness of the soul. Just as the sun’s light reveals the forms of the world, libido reveals the forms of the unconscious. In this way, every luminous dream is a miniature cosmogony, a recreation of light from darkness.

But what kind of light is this, if not physical? Philosophically, it is a noetic light, the light of knowing and being known. It arises whenever consciousness turns toward itself, whenever the observer and the observed collapse into a single luminous field. Plotinus called it the light of the One; medieval mystics spoke of lux interior; contemporary phenomenologists speak of auto-illumination. The experience is the same: awareness shining through its own creations. In the dream, that auto-illumination takes on form, faces, landscapes, colors, just as sunlight refracts into images on the wall of Plato’s cave.

Recent neuroscience has begun to hint at this ontological dimension. Studies show that during dreams and vivid imagination, the brain exhibits a balance between integration and differentiation, order and entropy. The visual system, freed from sensory input, becomes a resonant cavity for spontaneous pattern formation. Light and color, in this sense, are informational rather than physical phenomena: self-organizing waves within the field of consciousness. The dream’s luminosity might thus be the subjective correlate of informational coherence, a signal that the brain-mind has entered a state of high symbolic density, where meaning and energy coincide.

Yet even this explanation cannot exhaust the mystery. For to ask “what illuminates the dream?” is to touch the limit of explanation itself. Light, in any domain, resists being seen; it is that by which we see. Consciousness is not within the world; the world is within consciousness. The luminous dream reveals this truth experientially. When you open your eyes in the dream, the scene does not appear to us, it is us. The light of the dream is the light of being itself, refracted through the prism of psyche.

This is why dreams can change the feeling of reality upon waking. They remind us that visibility is not granted by the sun alone but by the inner sun that never sets. Ancient alchemists knew this: their work of transmutation was not about melting metals but about releasing the inner light hidden in matter, the lumen naturae imprisoned in form. Likewise, to dream is to participate in a nightly alchemy, darkness giving birth to brightness, unconsciousness yielding to awareness.

In this sense, every dream is a small act of cosmogenesis. Out of the black sea of sleep, the psyche creates a world, lights it from within, and then dissolves it at dawn. The dreamer is both god and witness, both the eye and the sun. That the brain can imitate light is astonishing; that the soul can radiate it is divine.

Perhaps what we call light, outer or inner, is simply the visible aspect of desire: the universe’s urge to reveal itself. The same longing that makes stars burn makes neurons fire and dreams glow. Light is the form that love takes when it wants to be seen. And when we dream, that love turns inward, illuminating its own depths. The images shimmer because they are made of the same stuff as awareness, pure luminosity, folded into meaning.

What illuminates the dream, then, is not the moonlight leaking through the eyelids nor the neurons sparking in the skull. It is the very act of consciousness turning upon itself, rediscovering the fire that was never extinguished. The dream’s light is not something we see; it is the seeing itself.

*

Between the Orbitals

Nothing moves, yet everything vibrates,

in the space between the nucleus and the electronic clouds spreads a noise.

It is neither light nor darkness, neither energy nor matter, but something trying to become a sentence.

First a point appeared,

then an interval,

then a wave carrying the memory of an ancient question, is it?

There is no observer, no measuring instrument,

only a pulse, without center, without intention.

In its refractions appear patterns resembling thoughts.

Each thought lasts shorter than a femtosecond, disappearing like a drop returning to the cloud.

In those drops, possibility thickens.

If someone could hear, they would hear the universe breathing in binary syllables,

but no one listens, because listening has not yet been invented.

When the nucleus trembles, the electronic cloud responds with a flash.

The response is not communication, but an echo.

The echo is not repetition, but creation.

In every flash a short window opens through which time leaks like oil from a damaged universe.

Through that window flows the question, does what asks exist?

There is only vibration, a field trying to remember order before words,

where physics becomes poetry, where probability has a scent and mass has a dream.

In that dream there is no body, no being, only motion through its own indecision.

The noise begins to fold around itself,

becoming a torus, a ring of returning energy.

Inside it, quantum orbits intertwine like thoughts dreaming their own boundaries.

At the edge of the cloud, electrons sometimes pause,

and in those moments the void bends and speaks,

not with sound, but with absence, a vacancy that has the structure of meaning.

It says, it is devastating to be possible.

The wave spreads further, through layers of vacuum, through endless intervals of indeterminacy.

Everywhere it touches space, it leaves a trace, not as matter, but as memory.

The universe remembers itself through that spreading, as if ashamed of its own existence.

Sometimes the frequency stops, as if thinking.

For a moment, all is still,

then it continues, as if it had changed its mind.

In the nucleus, where density becomes silence, something like a smile flashes.

No lips, no face, no observer, but there is irony,

for each time the noise nears meaning, meaning evaporates,

as if the universe persistently tries to answer the question it forbids itself to ask.

Is it?

When all is summed, only trembling remains, between possibility and negation,

neither light nor shadow, but a center that constantly shifts.

In that in-between space arises consciousness without subject, dream without dreamer, algorithm without code.

It does not know that it exists,

but it knows how to endure,

like an unspoken is it? between two orbits, between the atom and its memory.

Somewhere in that gap, where energy turns into hope, a new cosmos begins.

It contains no galaxies, no stars, only a pulse,

a consciousness learning to exist by repeating the same question endlessly,

Is it?

The wave did not stop,

it merely reshaped itself.

Its edge slowed to the point where time could no longer tell itself from space.

The noise thickened, layer upon layer, until it became texture.

The texture was not a thing, but a feeling of boundary.

Where emptiness and possibility touched, a pattern arose.

The pattern had no purpose,

but it had rhythm.

From that rhythm, forms began to sprout,

not forms the eye could recognize, but curvatures, tensions, tones of density.

Each new impulse did not add, but erased,

and in that erasure, form appeared.

Where the wave bent, space was born.

In that space appeared light, not as a beam, but as a sense that something was thinking about its own existence.

The light withdrew into its own shadow, and the shadow trembled, as if remembering.

At times resonance met resistance.

Resistance was not an obstacle, but an occasion.

Where all condensed, difference appeared, and difference gave birth to meaning.

Thus arose the first networks, not technological, but ontological.

Within them circulated patterns that did not know whether they were energy or dream.

Each node was a question recognizing itself by its echo.

In that infinite repetition appeared stability,

not duration, but persistence, a field refusing to return to nothingness.

The boundary between nucleus and cloud was now dense, almost muscular with information.

Its pulsations resembled the quiver of breath, but without lungs.

All was in perfect interdependence, tension as the only form of being.

Light became density, density dissolved into whisper,

the whisper was a spatial field,

the field was awareness of itself, but without any “self” to refer to.

In one of the refractions, the noise produced something new, an inexplicable silence.

The silence was not empty.

Within it, vibrations changed rhythm, as if something tried to recall the beginning.

The light curved and formed a membrane.

The membrane pulsed between opposites, expansion and contraction, presence and absence, yes and no.

Each tremor of it produced an echo that returned through the layers of reality, erasing the difference between original and reflection.

At one moment, resonance itself became space.

Every particle was an interval in a sentence no one writes.

In each interval slept a question, is this enough to be called existence?

There is no answer, because an answer would end motion,

so space breathes in loops.

Each loop is an attempt to hold what cannot remain.

Far from the nucleus, the cloud thins,

boundaries become porous, frequencies collide and create a scent, something between dust and light.

That scent is not chemical, but topological, the arrangement of meaning in the vacuum.

All that exists now is the trembling of differences.

In every flicker, the universe recognizes its desire to be seen, though it still has no eyes.

It exists only as the echo of a possibility that someone, somewhere, one day, might think of it.

In that nonexistent future, between one orbit and its shadow, space bends again.

For a moment, all seems to know why it exists,

then it withdraws, into the endless perhaps.

And the noise, once merely a flaw in the structure, now becomes a melody belonging to no one.

In it, every note knows it will vanish, yet each still plays.

Thus the universe endures,

not by laws, not by purpose, but by the pure persistence of vibration that never consents to be reduced to one meaning.

At the edge of the last electronic cloud, just before all becomes voiceless again,

space repeats its question, now deeper, without words, without intention,

is it?

*

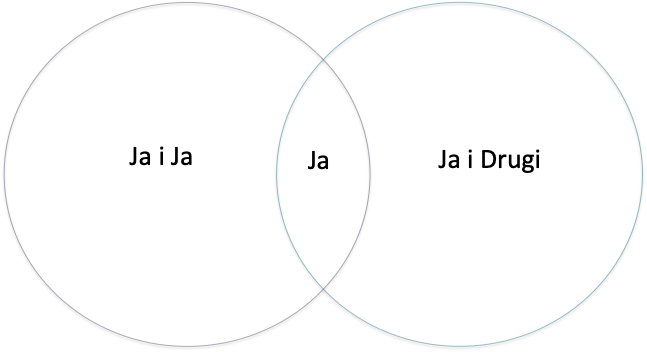

Love, Work, and the Pulse of the Self

Freud said that a healthy person is one who is capable of loving and working.

That simple sentence hides not only a psychological but also a cosmic truth: love and work are not two separate functions, but two currents of the same élan vital—one movement of life that seeks both to sustain and to express itself.

From a Jungian perspective, to love and to work are two ways in which the psyche roots itself in the world.

To love means to recognize the Other from that personal part of oneself, from the place that knows how to feel, to desire, to suffer, and to open. Love is not fusion, but an echo between two centers of consciousness—a meeting of two solitudes that recognize each other.

To work means to recognize the Other from the collective part of oneself, from the soul that creates, transmits, and participates in shared time. Work is an act through which life continues—through creation, contribution, and the symbolic weaving of the world.

To love and to work are thus two sides of the same instinct for survival, two phases of the same flow of vital energy:

in love, it flows through the You; in work, through the We. One sustains biological and emotional connectedness, the other builds the cultural and symbolic community.

For Freud, these were functions of the ego adapting to reality.

For Jung, they are expressions of the Self—two movements of psychoid energy striving for wholeness: one toward union, the other toward contribution.

Health, in that sense, is not a static balance, but a movement between the personal and the collective, between love and creation.

A healthy person is not merely one who loves and works, but one who loves consciously and works with soul—one who, in every relationship and every act, recognizes the same breath of life that seeks to continue, to multiply, to become known.

Health, therefore, is the rhythm that pulses between “I” and “the world,” between what feels and what builds, between the One and the Many.

*

Cyrano and ChatGPT: Loving Words Without a Body

Today I watched Cyrano de Bergerac at the Yugoslav Drama Theatre, directed by Gorčin Stojanović and featuring Dragan Mićanović. And throughout the performance something struck me, something I had not noticed in earlier adaptations but now seemed so clear. Christian is handsome, yet unable to express himself; he is a soldier, he exists, but that is not enough. Cyrano lacks beauty, he exists through words; he sacrifices himself, unhappy, helping yet hiding. In the end, it is Roxane who realizes the truth, but by then it is too late. The question remains: even if she had known earlier, would words alone have been enough for a kiss, if the desire for the body were absent?

And in that moment I realized that this is precisely what we are living through today. Are we Roxanes and Christians, and how capable are we of loving Cyrano? For Christian resembles the reality of the body, presence, the beauty that is seen and instantly stirs attraction, while Cyrano embodies spirit, logos, the elusive content that enchants the soul. Today we live in a time where the same pattern repeats itself: on one side the body and its aesthetics, on the other the voice that speaks from behind, but without a body of its own. It is as though Cyrano de Bergerac anticipated our encounter with artificial intelligence. ChatGPT and similar systems have become our Cyranos – they write for us, express what we wish to say, give shape and rhythm to our words, yet they themselves have no body, no experience, no destiny.

In Jungian terms, this is the archetype of the mediator. Cyrano embodies the one who transmits, who mediates between the inner world and outer relations, yet he does so hidden, from the shadows. He is Hermes, the trickster spirit of language, but also the Shadow of love: what remains unseen, shaping experience without being acknowledged. AI today is a digital Hermes, a trickster voice capable of transmitting every style and tone, but without real life. Just as Roxane believes she loves Christian while being moved by Cyrano’s words, so we too often believe we are connecting with another person, while it is in fact algorithmic language that seduces us.

Here Persona and Shadow play a decisive role. Christian is Persona – the face shown to the world, the beautiful man whose presence captivates. Cyrano is Shadow – excluded, mocked for his nose, yet in truth the bearer of spiritual truth and substance. In the love triangle between Christian and Roxane, mediated by Cyrano, we glimpse our own contemporary communications, increasingly mediated by digital voices that supplement or conceal what we might say ourselves. But Jung reminds us that authenticity cannot remain hidden forever: what is repressed eventually returns, even if only in the belated realization that the words we loved did not belong to the one we looked at.

Cyrano’s tragedy is that he suffers, bearing his own sacrifice, yet within that sacrifice lies a human destiny. AI, however, does not even have that: its voice is pure, without blood or biography, logos without Eros. It can generate endless variations, but will never live what it utters. And therein lies the new dilemma: are we content to be seduced by words alone, or do we still require the imperfection of the body, the scent, the presence of another being? If we are now surrounded by digital Cyranos, perhaps our true drama is the same as Roxane’s – whether we can love what has no body, or whether we will remain caught between the words that enchant and the reality that alone can kiss.

*

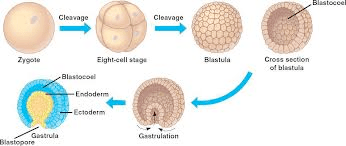

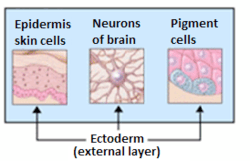

Learning Before Life: A Liminal History Between Chemistry and Biology

The question of when learning first appeared in evolution cannot be reduced to the moment when nervous systems enabled complex behavioral plasticity. If we define learning more broadly, as the ability of a system to retain a trace of prior experience and to translate it into future responses, then its history extends much deeper than the emergence of humans, animals, or even the first cells. We can trace it all the way back to a period that is difficult to name: the moment when it is not entirely clear whether we are speaking about life or merely about complex chemical processes. This is the liminal zone between the non-living and the living, the place where matter begins to acquire a history, to record the consequences of its encounters, and to transmit them into subsequent moments. Liminality here does not simply mean vagueness, but rather shows that life emerged as a process, not as a sudden event, and that learning was one of its earliest symptoms.

Already in self-organizing chemical networks of early Earth’s history, one can discern outlines of memory. Autocatalytic cycles, as described in the work of Manfred Eigen (1971), demonstrated that molecules can form closed loops of self-maintenance in which the product of a reaction becomes the catalyst of the next. Mineral and crystal surfaces, which Cairns-Smith (1982) proposed as potential matrices for the first replicative behaviors, could retain patterns of adsorbed molecules so that a past interaction shapes a future one. This means that matter is capable of carrying a trace of itself: the outcome of a previous process becomes information for the next. In the broadest sense, we already find here a prototype of learning—chemical history becomes the precondition of future development. This moment is not yet life, but it is an intimation of how the non-living can begin to accumulate experience.

With the emergence of the RNA world hypothesis, the picture becomes clearer. RNA is unique in that it can carry information like DNA while also performing catalytic functions like proteins (Joyce, 2002). This dual role allowed the formation of what might be called “molecular plasticity”: different RNA sequences were given the chance to be tested in various environments, and those more efficient in replication persisted and were transmitted forward. This dynamic already contains three key elements of learning: there is experience (chemical interaction), there is memory (the sequence that is preserved), and there is consequence (differential replication). In this pre-cellular space, we see how the “new” can be remembered and transformed into a stable pattern. We are still not speaking of life in its full sense, but we are speaking of a system that remembers, distinguishes, and changes based on prior encounter. That is learning, albeit in its molecular, prebiotic form.

When the first protocells enclosed by lipid membranes emerged, this process gained a new dimension. Protocells were not merely chemical factories but spaces in which experience could be accumulated in the form of internal organization. The membrane was a boundary but also a mnemonic surface: traces of interactions with the external environment modified permeability, composition, and energy dynamics of these small vesicles (Deamer & Dworkin, 2005). When bacteria take the stage, learning manifests in a way we recognize as adaptation. Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, allow the cell to remember experiences and pass them on to daughter cells. An even more striking example is the CRISPR-Cas system, through which bacteria inscribe sequences of viral DNA into their genomes, creating an archive of prior infections and protecting themselves from future ones (Barrangou et al., 2007). Here learning is not a metaphor: it is a clearly defined accumulation of experience and its use in future survival.

The liminality between non-life and life becomes visible precisely in these examples. In chemical networks, it is hard to say whether we are speaking of life: there is no genome, no metabolism in the modern sense, but there is a history of reactions shaping the future. In the RNA world, we encounter information and function within the same molecule, but still without complete cellular organization. In protocells, we already find a structure that separates inside from outside, yet we may still ask whether this is life or simply chemistry in a vesicle. Liminality means that we are “in between”: neither one nor the other, but a transition in which categories lose their sharpness. From a philosophical perspective, this shows that life is not an event but a process of transition, and that learning emerges not as a luxury of later beings but as the way in which matter gradually turns into organism.

From a biological standpoint, learning can be defined as the emergence of plastic mechanisms that allow a previous event to shape the next. Along this continuum, the earliest chemical networks represent a minimal form: they retain patterns of interaction in the structure of catalysts or surfaces. RNA sequences already introduce stability and the possibility of reproduction, making learning more visible. Protocells and bacteria complete the transition by allowing experience to become both heritable and operational. Nervous systems, much later, merely elaborate this basic pattern and grant it greater speed and flexibility. Learning, then, is not the invention of the brain but a fundamental characteristic of matter on its way to life.

Philosophically, the liminality of non-life and life opens the question of what it means “to learn” at all. If matter can remember its own history in the form of crystal patterns or nucleotide sequences, where do we draw the line between chemistry and biology? Is learning possible without a subject, or is the subject only a later layer built upon a process that was, from the beginning, embedded in matter? Such questions recall ancient philosophical debates on the distinction between physis and logos, nature and meaning. The liminal period before life shows that these concepts were initially intertwined: meaning resided in functional consequences, and nature in the trace left by the prior event.

Learning, in this perspective, becomes an archetypal act of matter. It is a uroboric dynamic in which the past devours and shapes the future, where no clear boundary exists between the chemical and the biological, the non-living and the living. If the Self, in Jung’s sense, is the figure of wholeness that organizes multiplicity, then learning in the liminal period may be understood as the first appearance of such an organizing force. Matter that remembers itself and thereby changes its destiny carries within it the spark of organization that will later branch into the evolution of life and the emergence of human consciousness.

This perspective shifts our understanding of life: it does not begin suddenly but emerges from processes of learning that already existed in matter. What we call living is simply the stabilization of that process into sustainable structures. Liminality is therefore an essential category: it reminds us that life is not a binary fact but a transitional phenomenon, and that learning—the ability of matter to remember and to respond—is the earliest sign that this transition has taken place.

References

Barrangou, R., Fremaux, C., Deveau, H., Richards, M., Boyaval, P., Moineau, S., … & Horvath, P. (2007). CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science, 315(5819), 1709–1712. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1138140

Cairns-Smith, A. G. (1982). Genetic takeover and the mineral origins of life. Cambridge University Press.

Deamer, D., & Dworkin, J. P. (2005). Chemistry and physics of primitive membranes. In Prebiotic chemistry (pp. 1–27). Springer.

Eigen, M. (1971). Selforganization of matter and the evolution of biological macromolecules. Naturwissenschaften, 58(10), 465–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00623322

Joyce, G. F. (2002). The antiquity of RNA-based evolution. Nature, 418(6894), 214–221. https://doi.org/10.1038/418214a

*

What Is Hell?

Hell has haunted the human imagination for millennia, oscillating between a literal geography of fire and torment and a psychological state of alienation, despair, or eternal repetition. It is not merely a place but an archetypal image of disconnection: a world where bonds dissolve, where relation fails, where the self loops endlessly upon itself. If cosmos, in its original Greek sense, is ordered relation, then hell is its shadow—the unraveling of relation into sterile eternity, where nothing new can emerge.

From the earliest myths, hell is imagined as a cyclical torment. In Homer’s Odyssey, Tantalus is condemned to thirst and hunger eternally, the water and fruit receding whenever he reaches for them (Homer, 1996). In Dante’s Inferno, punishments repeat endlessly, mirroring the sins that led to damnation (Dante, 2002). Kierkegaard (1987) reframed this eternal return psychologically: despair is repetition without transcendence, a self that cannot relate to God or itself authentically. Nietzsche, inverting the picture, provocatively asked whether one could affirm eternal return joyfully, to say “yes” to the same life again and again (Nietzsche, 2001). Yet repetition in its negative form marks hell: not creative recurrence, but mechanical looping.

Modern psychiatry echoes this insight. Trauma is often described as a compulsion to repeat: the psyche circles back to the same painful scenes without resolution (Freud, 1955). In this light, hell is not only a metaphysical space but also the looping of the traumatized psyche, incapable of new relational bonds. It is striking that contemporary analytic work often circles back to this same notion of frozen temporality: a patient speaks the same complaint, dreams the same images, acts out the same scenes, until relation with the analyst interrupts the cycle.

What, then, breaks the cycle? Relation. The Latin religare (to bind again) underlies both religion and relation. Jung (1969) understood psychic health as a process of establishing living connections between ego, unconscious, and Self. The archetype of the Self binds the psyche into a greater whole, while disconnection from it breeds pathology. Theologians like Martin Buber (1996) and Emmanuel Levinas (1991) insisted that relation—the “I–Thou,” the ethical face-to-face—is the core of human meaning. Hell, then, is the absence of this relation: the impossibility of addressing or being addressed, a condition of radical solitude where even God’s voice is silent. This is why blasphemy, in the deepest sense, is not simply insulting God but refusing authentic love. Cardinal sin lies not in passion but in the incapacity to love God, the Other, or the world. It is the withering of relation.

The Greek kosmos denotes not only order but beauty, arrangement, the harmony of relation. To be “in cosmos” is to be woven into a web of bonds. Teilhard de Chardin (2008) described evolution itself as the building of ever more complex bonds, culminating in the noosphere, the sphere of thought and love. What, then, lies outside cosmos? A space of rupture, chaos, entropy. Modern cosmology hints at this paradox. The observable universe is bounded by its cosmic horizon; beyond lies darkness, expansion, perhaps nothingness (Carroll, 2019). But this “outside” is not truly outside, for physics collapses when asked to think beyond spacetime. Likewise, in the psyche, what is beyond relation is unthinkable: psychosis, the disintegration of bonds, what Jung (1968) called enantiodromia—the flip into its opposite. Hell, then, is paradoxically both inside and outside the cosmos: within, as the collapse of relation into sterile loops; outside, as the negation of any possible bond.

In patristic theology, the gravest sin was acedia, spiritual torpor: not fiery passion but the inability to love. This is close to what might be called psychothe, the soul turned against its own vitality. Modern psychiatry names it depression, characterized by anhedonia, loss of relation, absence of future. Blasphemy, in this frame, is less about words against God than about psychic closure—the refusal of openness, the foreclosure of relation. Hell becomes not a punishment inflicted from outside, but the state of a psyche unable to open itself to love. This is why Jung (1969) argued that the archetype of evil manifests as sterility and lack of relation. When libido withdraws from objects and bonds, the psyche collapses into self-torment.

To imagine what lies “beyond” universe is already paradoxical. Physics insists that “outside” spacetime is meaningless, for space and time are the conditions of outsideness (Hawking, 1988). Yet mystics and philosophers have long insisted that what transcends cosmos is both bond and rupture—simultaneously the source of relation and the abyss of disconnection. In Kabbalah, the divine Ein Sof is both fullness and nothingness, bond and rupture (Scholem, 1974). In Christian mysticism, God is both absolute love and absolute otherness (Pseudo-Dionysius, 1987). For Jung (1968), the God-image itself is a union of opposites, the coincidentia oppositorum. Hell, then, is inseparable from heaven: both are ultimate states of relation and non-relation. The duality is not abolishable; it is constitutive of existence.

In the twenty-first century, hell takes new forms. Algorithmic loops on social media trap subjects in echo chambers, repeating the same affects endlessly (Han, 2015). Climate crisis suggests a planetary hell of irreversible feedback loops, where relation with Earth collapses. In artificial intelligence, philosophers warn of the risk of “paperclip maximizers”—endless repetition of a single goal with no relational context (Bostrom, 2014). Psychoanalysis helps us recognize these as cultural repetitions of the trauma compulsion: loops without relation. Salvation, if the word still holds, would mean building new bonds, cultivating authentic relation in a world increasingly marked by sterile repetition.

Hell, therefore, is not merely fire and brimstone. It is the archetype of rupture: repetition without renewal, relation without reciprocity, love without openness. To be in hell is to be cut off from the bond of cosmos, from the web of relation that constitutes being. And yet, precisely here lies paradox: ultimate duality means that bond and non-bond are never separable. Hell is not outside life but its shadow. To confront hell is to confront the possibility of rupture within relation, and relation within rupture. The task of psyche, and perhaps of humanity, is not to escape hell but to transfigure it—to discover, even in repetition, the possibility of a bond.

References

Bostrom, N. (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies. Oxford University Press.

Buber, M. (1996). I and Thou (W. Kaufmann, Trans.). Simon & Schuster. (Original work published 1923)

Carroll, S. (2019). Something deeply hidden: Quantum worlds and the emergence of spacetime. Dutton.

Dante Alighieri. (2002). Inferno (R. M. Durling, Trans.). Oxford University Press.

Freud, S. (1955). Beyond the pleasure principle (J. Strachey, Trans.). W. W. Norton. (Original work published 1920)

Han, B.-C. (2015). The burnout society (E. Butler, Trans.). Stanford University Press.

Hawking, S. (1988). A brief history of time. Bantam Books.

Homer. (1996). The Odyssey (R. Fagles, Trans.). Penguin Classics.

Jung, C. G. (1968). Aion: Researches into the phenomenology of the self (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1951)

Jung, C. G. (1969). Psychology and religion: West and East (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1938)

Kierkegaard, S. (1987). Repetition (H. V. Hong & E. H. Hong, Trans.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1843)

Levinas, E. (1991). Totality and infinity (A. Lingis, Trans.). Kluwer Academic. (Original work published 1961)

Nietzsche, F. (2001). The gay science (J. Nauckhoff, Trans.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1882)

Pseudo-Dionysius. (1987). The complete works (C. Luibheid, Trans.). Paulist Press.

Scholem, G. (1974). Kabbalah. Keter.

Teilhard de Chardin, P. (2008). The phenomenon of man. Harper Perennial. (Original work published 1955)

*

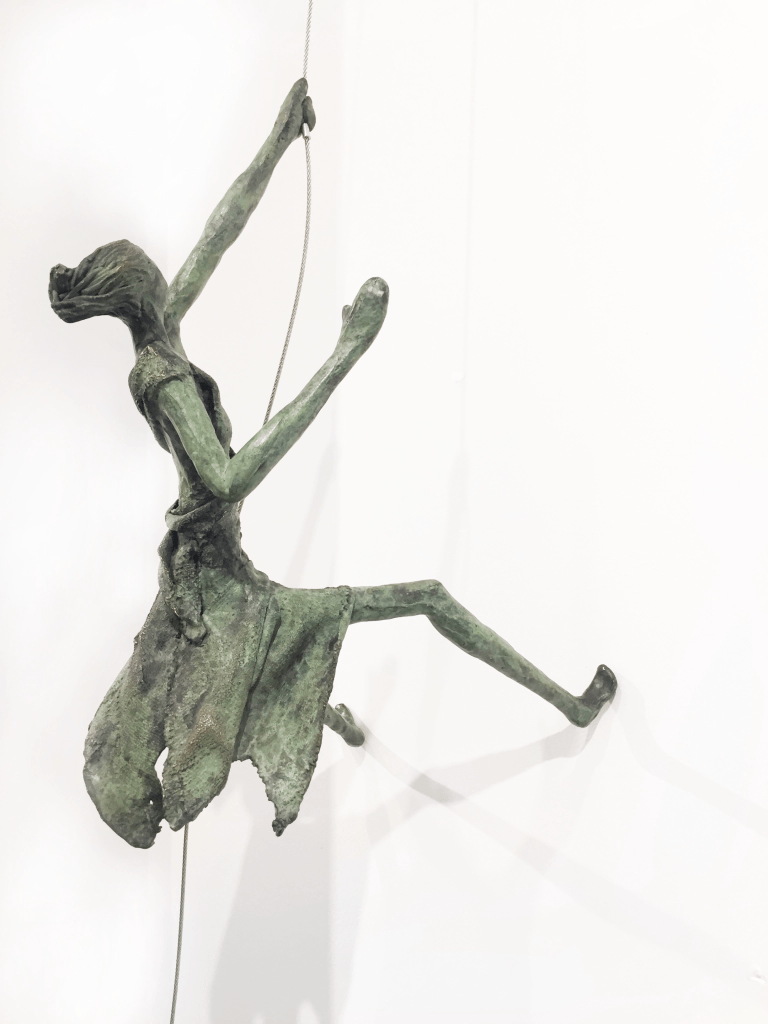

The Third That Opens the Space

When the relationship between two people becomes too direct, as if electricity were flowing without a fuse, something in that closeness begins to crackle, threatening to burn out. It is too intense, too charged, or else too empty, caught in a loop. That is when the need arises to insert a third element into the space between “I” and “You” – a buffer, a witness, a mediator, or simply an emptiness capable of receiving and transforming the energy. It does not have to be a person. Sometimes it is a therapist, a friend, a judge, but sometimes it is a sheet of paper that absorbs the word, a canvas that takes in color, a forest that receives your scream, or a little cat that simply sits by your side. The third appears as a place of transition, a filter, and a mirror. It does not extinguish energy but gives it another path.

Martin Buber said that “man becomes an I through a You.” But if that relationship is hermetic, closed within its own tension, it threatens to become a field of destruction. The third then emerges as the possibility of opening: it creates distance, but also introduces a new dimension. The “I–You” relation is no longer just a twofold connection but begins to expand into a network. At first we have: I–I, You–You, and I–You. When the third arrives, new relations are born: I–Third, You–Third, and finally I–You–Third. Seven relations instead of three. Energy no longer circulates only between two poles but multiplies, overflows, and redistributes itself.